As Jimmy Hall tells it, after nearly a week of searching for his son, he no longer expected to find him alive.

“I had pretty much given up all hope,” he told me on a recent afternoon. “I started checking in the woods and in the creek. My parents started looking in the dumpster. At that point, I was searching for a body. I was searching for my son’s body.”

Hall had plenty of reasons to let that dark thought settle in his mind at the time. He knew the odds were against his son, Rashawn Williams, a 31-year-old man with Down syndrome who doesn’t speak much and wouldn’t be able to ask for help.

After Williams slipped away from his caretaker and boarded a bus, then a train, Hall and other family members searched from Maryland to D.C. for him. They searched through the night and woke up early to start searching again, and as they searched, they watched one day turn into four days and four days turn into six days.

“The gap just widened and widened and widened,” Hall recalled. “We were just waiting and waiting and waiting.”

If you followed Williams’s story at the time, then you know how it ended — unexpectedly. On that sixth day, he was found in a room down a corridor at a Metro stop. He had gone without water or food for nearly a week, but he was alive and, miraculously, he was healthy.

It would be easy for Williams’s family to focus on that happy ending and move on. But Hall said they can’t because they know how the search started — unacceptably.

Hall and his wife, Christina Hall, said after they learned that Williams was missing, they expected their phones to buzz with an alert that would let the public know to keep a look out for him. When that didn’t happen, Christina Hall asked an officer to send one. The couple said that’s when they learned that Williams did not meet Maryland’s criteria for an Amber Alert, which is for abducted children, or a Silver Alert, which is for adults over the age of 60 with cognitive impairments. The couple is now trying to bring attention to that gap in the state’s alert system in hopes of pushing officials to find a way to send public alerts when disabled adults who are at serious risk of harm go missing.

“We were fortunate,” Hall said. “But what about the next family? What about the next individual who goes missing? Because it will happen again.”

Hall said he has no doubt that if an alert had been sent immediately after his son’s disappearance, he wouldn’t have spent six days alone in a dark space, cold, thirsty and hungry.

“He would have been found that night,” Hall said. People look at their phones when they ride the bus, so those people on the bus with him would have seen the alert, he said. So, too, would have the people who rode the Metro with him. “He rode the train for over three hours. He came in contact with maybe 1,000 people that night. Somebody would have noticed him.”

The family’s call for an expanded alert system is one that warrants our attention, especially when we consider how easily Williams’s story could have ended differently. If he had not survived, we would be demanding an examination of the actions and inactions that took place after his disappearance. But it shouldn’t take a death to get us to collectively consider where the system could make improvements.

Williams’s family is trying to get us to see now — before it’s too late and our outrage is mixed with mourning — what they saw during their most panicked moments: an alert system that held no place for him.

Christina Hall said the days that followed his disappearance, she got bombarded with questions from people who wanted to know why she wasn’t requesting an alert. “I’m trying,” she recalled telling them, “but he doesn’t qualify.” She said she asked the police if an exception could be made for him and was told no. (Police shared a missing person’s poster of Williams on social media and with news outlets, but it did not mention he has Down syndrome or indicate that he was vulnerable.)

The Maryland State Police, which established the state’s Silver Alert program, lists among the required criteria: “The missing person is at least 60 years of age.” The national requirements for an Amber Alert, which is aimed at helping abducted children, lists as one of the criteria: “The child is under the age of 18.”

Elena Russo, a spokesperson for Maryland State Police, sent me the national guidelines in an email, along with a statement addressing the police response. “Using all the resources available, the Maryland State Police disseminated the information, sharing it with the public and law enforcement agencies regarding the missing person, Rashawn Williams,” she said. “As a critically missing person, the MSP shared information to engage as many people as possible in the effort to safely locate him.”

A look at Silver Alert programs across the country show that the criteria vary by state. Some states have programs that allow them to issue alerts for people younger than 60, and some states have created separate alert systems for individuals with disabilities. Texas and Alabama have Endangered Missing Persons Alert programs that are designed to help adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

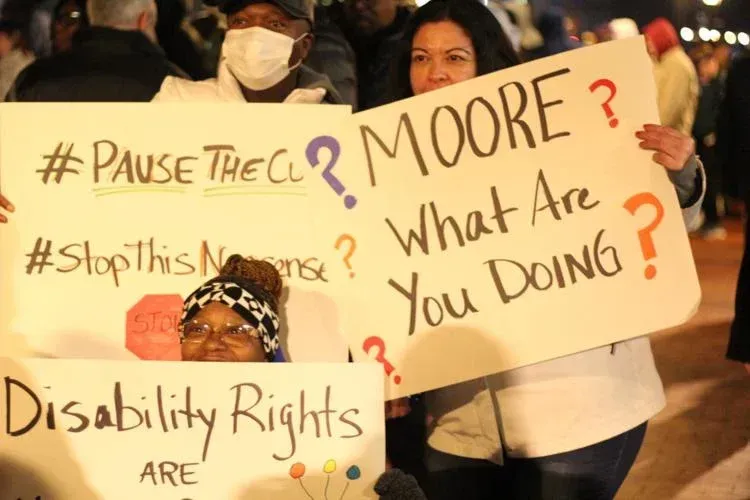

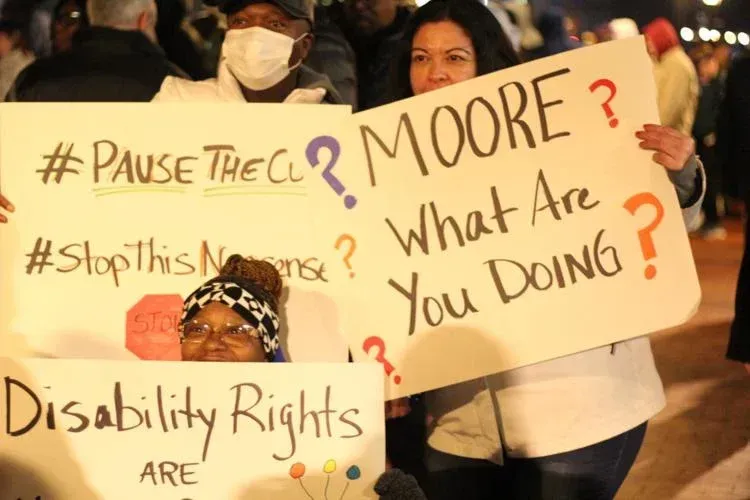

Those inconsistencies have not gone unnoticed by people with disabilities, their families or the organizations that serve them.

“Rashawn’s disappearance emphasizes the urgent need for updated Silver Alert laws that explicitly address and protect individuals with disabilities, including those with Down syndrome,” Michelle Sagan, of the National Down Syndrome Society, told me in an email. “It is crucial to introduce stronger, more inclusive language in these alerts to ensure the safety and swift recovery of our community members. Consistent and uniform Silver Alert laws across the nation is paramount in providing comprehensive support and protection for individuals with disabilities.”

Leigh Anne McKingsley, the senior director of disability and justice initiatives for The Arc, has spent the last several years working with Project Home Safe, a program aimed at reducing injury and death among people with dementia and developmental disabilities who wander from safe environments. The program encourages public discussion around issues such as locative technology — which can help locate a person who goes missing but can also take away some of their privacy when they aren’t in danger. McKingsley said in that same way. more conversations are needed around alert systems.

“We want to find out what really works,” she said. Too often, she said, “we kind of just do what we’ve been doing without having larger conversations around it in our communities.”

One argument against expanding alert systems is that if too many alerts are sent, people start to tune them out. But how many more would Maryland send if the alert system was expanded to include people with intellectual disabilities who are at high risk of harm? If 20 people on that bus with Williams had ignored the alert but five took notice, would that have been enough to get him to safety sooner? Would it make more sense for the state to expand its Silver Alert program or to create a new program?

These are questions we should be asking as a community. We should be asking them, because a family who just a few weeks ago was looking for a body are warning us about the stakes of ignoring them.

Address :

688 E. Main St. Salisbury, MD 21804

E-mail: whitney@UNA1.org

Toll Free Phone : 1-800-776-5694

Local Phone: 410-543-0665

Fax:

410-543-0432

To discuss employment opportunities in Cecil, Talbot, Kent, Dorchester, Worcester, please call: Heather Snell. (EXT. #103)