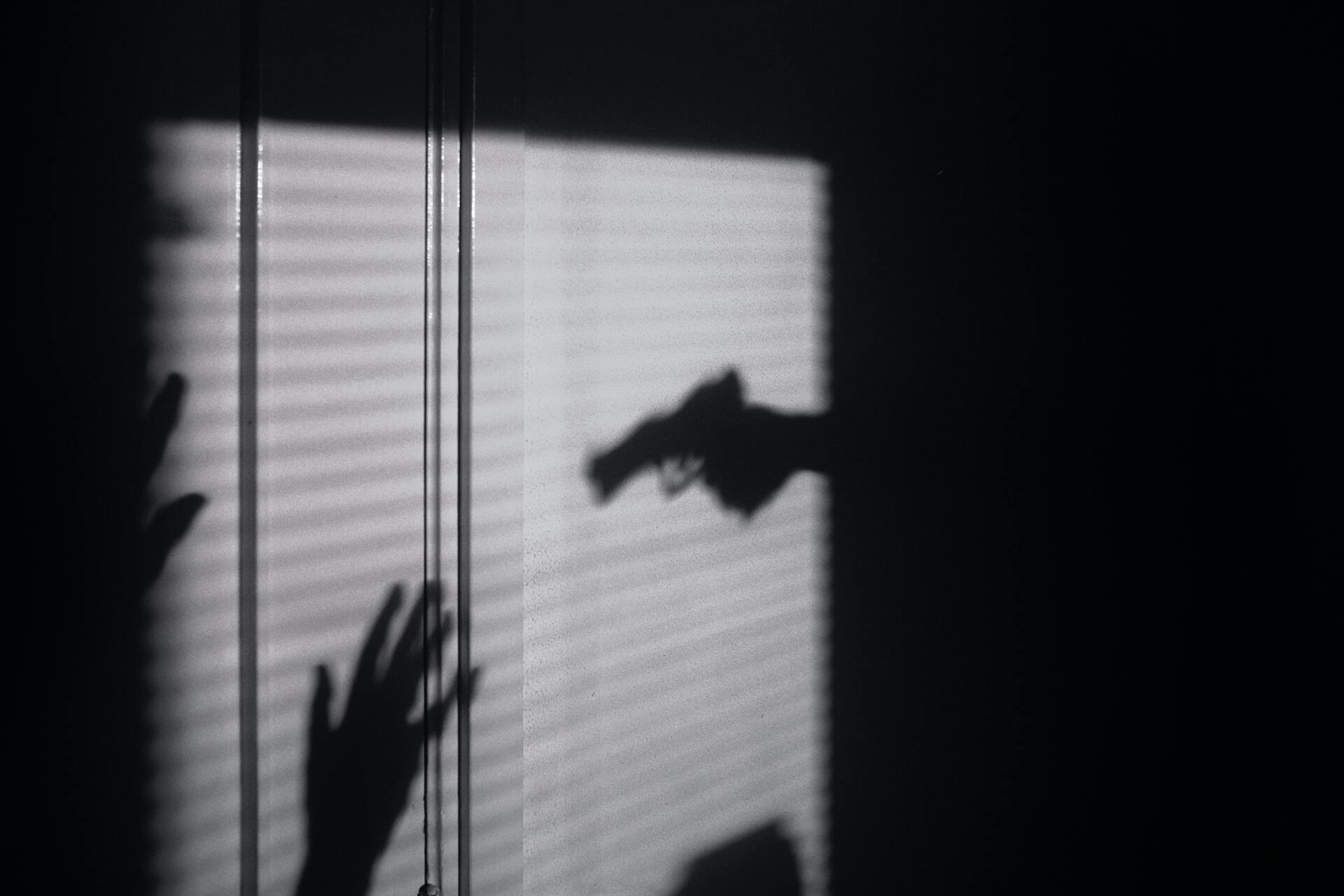

DELMARVA – People with disabilities face violence and crime at a disproportionately higher rate than able-bodied people, according to recent data [01] from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Between 2017 and 2019, disabled people accounted for 26% of nonfatal violent crimes, even though they make up just 12% of the U.S. population. People with disabilities are also victims of violence almost four times more than non-disabled people.

But that data isn’t a surprise for many disabled people, according to Ron Pagano. “I think now, you see so many disabled people standing up and speaking out. That’s because we have been empowered,” he said.

And recent statistics might not even paint the full picture. That’s because not everyone feels safe reporting those incidents, or they’re worried that no one will believe them. “They might go to the police but they’re not deemed to be a reliable narrator because they might have mental health issues or developmental, intellectual disabilities and are not believed,” said Executive Director of the ACLU of Delaware Mike Brickner.

Reporting can also depend on who the perpetrator is. “They are in close proximity to people that they are sort of forced to trust. Often times, they don’t always have mechanisms to be able to alert people about that abuse,” said Brickner.

Pagano says the risk of being harmed by a hired caretaker is a concern that some disabled people must weigh before making the decision to hire one. “You don’t always know who’s coming in. They say they check their backgrounds, but you don’t always know that,” he said.

For many in the disability community, vulnerability can lead to violence. Pagano says it’s an unfortunate, but very real fact he and others must live with. “I think it takes a lot of bravery to stand up and be able to say ‘I’m vulnerable,'” he said. “I don’t want to be vulnerable, but I am. I know that.”

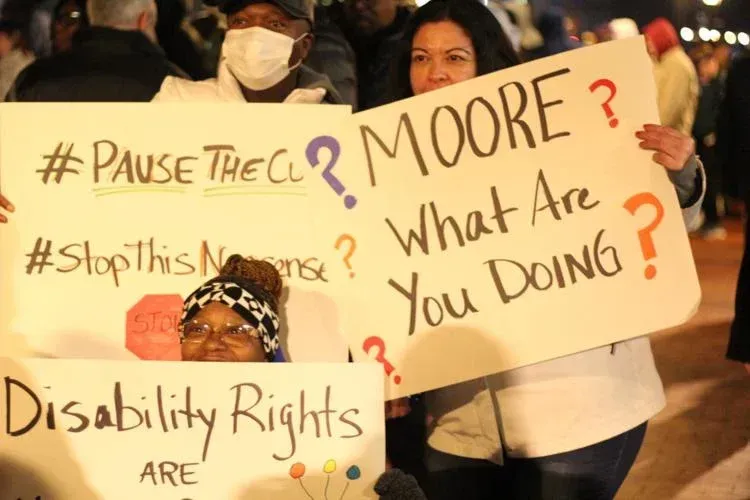

It’s also a pattern that’s deeply rooted in the roots of American history. “We’ve had eugenics and mass institutionalization of people with disabilities,” said Brickner. “We have a really bad history in terms of how we’ve treated people with disabilities.”

Brickner says many times, violence can rise from situations of unequal power dynamics. “Often times these crimes of simple assault are things like where the victim is hit because the caretaker thinks that they misbehaved,” he said. “We also sometimes see the phenomenon of people being groomed to be victims of crime. We see really high rates compared to the rest of the population.”

Dom Sessa says she’s seen how that inequity can lead to victims being silenced first hand. “I know so many people that have been victims of violence, that don’t even have access to proper education on how to defend themselves,” she said.

In addition, Sessa says disabled women, and those with cognitive or developmental disabilities are more likely than able-bodied women to be sexually assaulted. “With the physical limitations I have, it’s much easier when you’re disabled to be vulnerable – the way you maneuver, the way you get out,” said Sessa.

Brickner says a factor that plays into that could be a lack of effort to educate disabled people on sexuality. “We don’t typically tend to talk to those people about sexuality or knowing what the good and bad boundaries are in terms of sexual relationships,” he said. “So, then we see family members or caretakers or other people around them abuse them, and the person was never really empowered to be able to speak up for themselves.”

Violence against disabled people isn’t always as obvious as assault. Sessa says just a few years ago, something as simple as taking a trip to Walmart, quickly turned into a scary situation. “This guy came around really aggressively and held my chair. I was like ‘Can you let me go?’ and he wouldn’t let go. I had to scream because it’s me versus a 6’5″ man,” she said. “Imagine this is on the street. Imagine there’s not someone running toward you in the Walmart?”

Sessa adds that, to her, violence can be even more subtle than that. “Violence also exists in the way that disabled people are discriminated against in their every day existence,” she said. “Violence sometimes feels like being told that your quality of life is bad.”

While Pagano and Sessa say they don’t expect violence against disabled people to end any time soon, there are things we can all do to prevent it. And sometimes it’s as simple as just listening to those who are trying to speak up. “It’s not just a matter of hate, necessarily, although it is in some cases. It’s a matter of indifference,” said Pagano. “It’s a matter of not knowing. It’s a matter of feeling better when you can look down on somebody else.”

Having conversations with people different than you, and making an effort to come to a place of understanding is crucial, according to Sessa.

“I’ve had people that told me ‘Wow. I would rather die than live that life,'” she said. “We’re told sometimes our quality of life is poor in many forms. We accept that as ‘Well, if our quality of life is poor, we can’t change the landscape.’ But, I don’t accept that at all.”

Citations:

Address :

688 E. Main St. Salisbury, MD 21804

E-mail: whitney@UNA1.org

Toll Free Phone : 1-800-776-5694

Local Phone: 410-543-0665

Fax:

410-543-0432

To discuss employment opportunities in Cecil, Talbot, Kent, Dorchester, Worcester, please call: Heather Snell. (EXT. #103)